For awhile I didn’t know where to begin with this trip on the Hayduke Trail. This trip write up is a bit of a long one, covering our adventures over 250 miles and seventeen days, but I promise it’s a good one! Ever since the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), I’ve had the Hayduke Trail on my mind. However, the level of preparation and skill needed for the Hayduke Trail was something I didn’t have at the end of the PCT. I also wanted a hiking partner. Many areas of the trail are very remote and a second set of eyes is very valuable when assessing routes and situations. Several years after the PCT, I felt like I’d done enough more challenging trips and had a roommate crazy enough to go with me.

The Hayduke Trail is inspired by one of Edward Abbey’s book characters in The Monkey Wrench Gang, George Washington Hayduke. This route follows about 800 miles through Utah and Northern Arizona. Pieced together by Joe Mitchell and Mike Coronella, this trail is largely a route, connecting miles of desert canyons, remote roads, and trails. Starting in Arches National Park and ending in Zion National Park, there appears to be no rhyme or reason to the route, other than taking you through the most remote (but beyond scenic) parts of the southwest. Despite the winding nature of the route, the founders are very specific in their route descriptions, as in many places there’s only one place to enter or exit a remote canyon.

We started our section hike of the Hayduke at Round Valley Draw, located near Cannonville, UT. Our trip would end hiking out the South Kaibab Trail in the Grand Canyon. This section ended up a good introduction to the trail, as the navigation skills were relatively simple. We spent most of it walking in the bottom of canyons and washes or connecting dirt roads and established trails. In this section we traveled through Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Bryce Canyon National Park, Buckskin Gulch, a portion of the Arizona Trail (AZT), and a partial traverse of the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon portion of this route had us entering from the North Rim and exiting out the South Rim farther down the canyon. We also needed to cross the Colorado River in the canyon, bringing up the idea of carrying pack rafts for the last section to float ourselves across.

Many Hayduke hikers start their trek in the spring to enjoy more water, but then need to beat impending summer heat. Fall hikers enjoy cooler temperatures, but need to beat the first major snow storm.

Hayduke hikers often hitchhike into towns to resupply, but we opted for setting out supply caches to avoid going into town. The logistics of this trip were the most complicated I’ve ever set up. I set out three food caches: one at Willis Creek Narrows Trailhead, one about a half mile from US-89 on Buckskin Wash Road, and one in a bear box at Jacob Lake. The fourth cache was brought to us at Nankoweap Trailhead by Clay, along with our pack rafts and paddles. I also set a water cache at the UT/AZ border.

This section of the trail I completed with my best friend, Drew, and his partner, Chris. Drew and I have been on many other questionable adventures together and live together in the winter. Chris is an archeologist by trade (he has a master’s degree in archeology) and currently works on Carson Hotshots. He also has done several trips in Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument and has quite a bit of river running knowledge, so I was thrilled to have him along.

Guest appearances were made by my partner, Clay. An avid backpacker and outdoorsman himself, Clay was running logistical support behind the scenes. He helped me drop off all the caches, met us before hiking into the Grand Canyon with our final cache, and offered to pick up all the used caches while we were still hiking.

Over a month of preparations later and the usual last minute packing the night before, we were ready to start our trip.

After a five and a half hour drive, one time change, and a coffee stop in Page, Clay dropped us off at Round Valley Draw Trailhead. Round Valley Draw is in Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument and is one of the bigger slot canyons on the route. We had about a mile walking in a wash to reach the drops into the canyon.

Round Valley Draw is quite a way to start the trip. The first drop isn’t super big and we easily passed our packs down. The second drop is about seventeen feet, requiring hikers to chimney their way down. We lowered our packs with webbing for that one. Once in the slot canyon, we looked up at tan waves off rocks, standing in a space under three feet wide in some areas. The slot canyon fluctuated around us as we made our way through. We encountered large boulders to scramble down and at one point crawled through a small opening under a large boulder pile.

Round Valley Draw connected us to Hackberry Canyon. Once out of the slot canyon, we hiked through Hackberry with giant walls of white rock rising above us. With Drew and Chris for scale, you can see just how large the canyon grows. Hackberry starts off dry and sandy with no vegetation. Eventually it transitions, becoming filled with colorful cottonwoods and a pretty substantial amount of flowing water. We saw a beautiful sunset the first night we camped.

The next day, we finished hiking through Hackberry Canyon out to Cottonwood Canyon Road. We crossed the creek multiple times in the morning and found a group of cows looking lost. We also found a cabin with cacti growing out of the mud roof.

I’m always surprised how people suddenly appear at trailheads. After a day and a half feeling completely alone we suddenly saw day hikers and a couple of bike packers. We walked along the road until we came to the Paria River. From here, the Hayduke Trail turns north, following the river until it’s confluence with Sheep Creek. We probably crossed the river at least fifty times. Never crossing higher than my knees, our feet were constantly wet. We also had a few instances where shoes almost disappeared in the mud.

The afternoon finished off with checking out an old, stone building and cellar. The evening finished off with a vibrant sunset reflecting off the Paria as we set up camp.

The Paria is much siltier than Hackberry and our water filters ran noticeably slower. A clear spring does flow out of a pipe in the canyon wall, hidden behind some cottonwoods deeper in the canyon. We stopped to collect some cleaner water and spent a few minutes trying to figure out how someone could’ve possibly placed a pipe that far back into such a narrow gap.

Eventually, we left the Paria at a canyon confluence and followed Sheep Creek. A small, clear trickle, Sheep Creek quickly faded away.

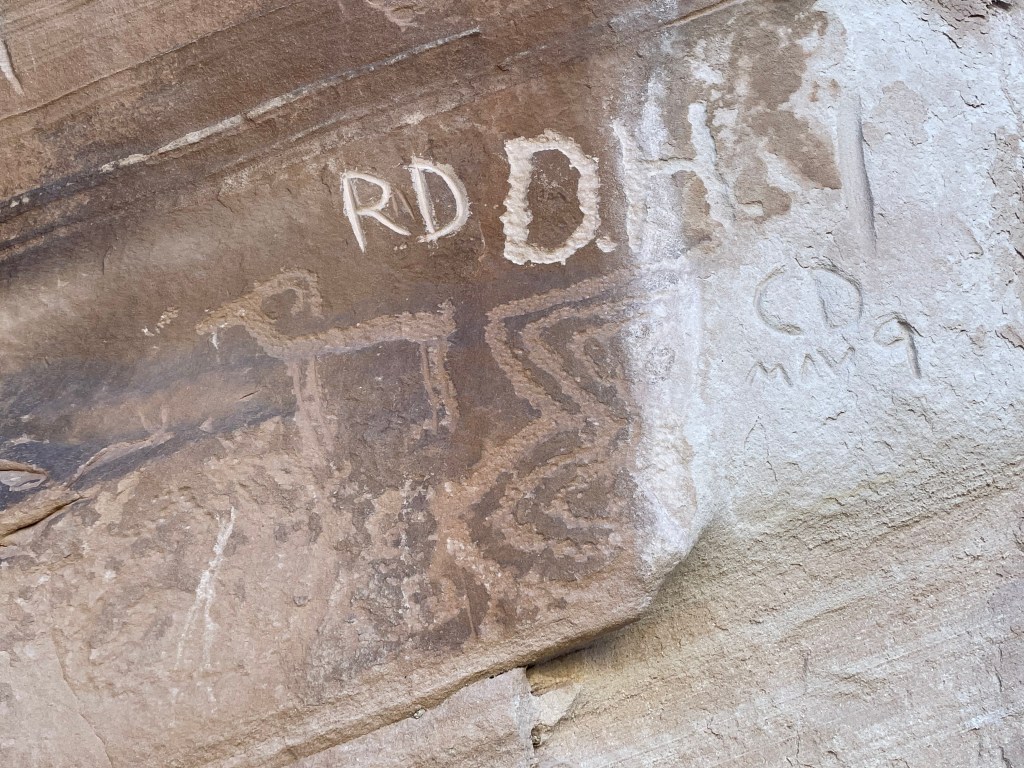

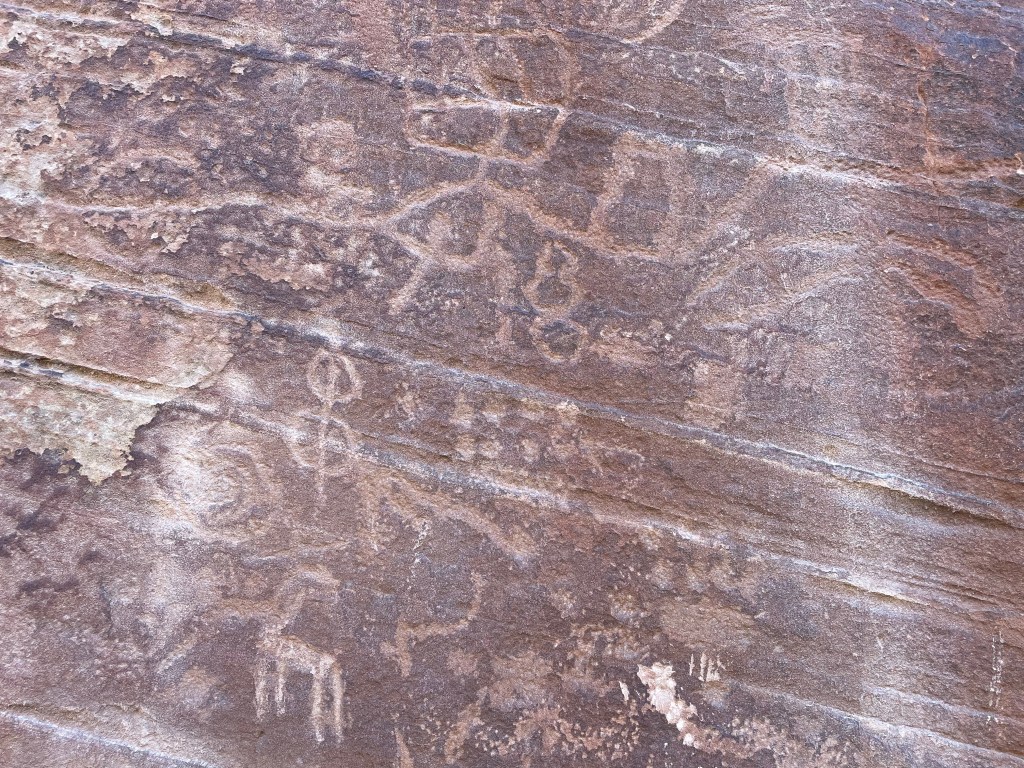

The dry canyon bottom took us to a petroglyph panel, popular for day hikers to visit. Chris, our resident archeologist, was thrilled as we took some time to examine all the images. Because of easy hiking access to the panel, it unfortunately has been vandalized by multitudes of people carving inscriptions around the petroglyphs.

After the petroglyphs we hiked through Willis Creek Narrows. As we wove our way through the waves of grey rock, I did my best to jump over every creek crossing. My shoes finally dried out and I planned to keep it that way. We arrived at the trailhead and retrieved the first cache I placed over a week ago. With everything intact we set up camp and planned to sort the cache in the morning.

The next morning we slept in before diving into the cache. We planned to only hike about nine miles this day, since we were approaching Bryce Canyon National Park. We didn’t have a permit to camp in the park, so we planned to camp just outside the boundary to hike through the park in one day.

A mostly uneventful day we walked down dirt roads and around a private piece of land. We made it about a half mile from the park boundary before setting up camp for a cold night.

Once we entered Bryce Canyon, we joined the Under the Rim Trail. We saw orange colored hoodoos from below mixed conifers. It was also unbelievably cold, even in the sun. We hiked up to Rainbow Point for lunch and decided to take a different trail that would reconnect us to the route. We traveled through Yovimpa Pass (off route) to Riggs Spring (on the route).

On our way out of the park we stopped at Riggs Spring to collect water. It took us awhile to scoop and filter enough of the stagnant, muddy water to refill our supply for the rest of the day. Once we exited the park, the route took us on another dirt road for several miles to the top of Bullrush Gorge. We picked our way through a field of sagebrush to a tucked away camp among juniper trees.

The next day we hike through Bullrush Gorge and past one of the best water sources we’d seen so far. The route descriptions details “a clear trickle coming out of the sand” and to fill up there, since almost no water exists on the route until reaching the AZT. We worried about this “trickle” existing, but sure enough, found a little stream running down the top of the gorge.

The gorge opens up to a large valley with remote jeep trails traveling along the bottom. We saw an old cowboy cabin nestled at the base of sheer white rock cliff faces. The cabin still contained old kitchen supplies and simple bedroom furniture. Drew told us at one point in time a cowboy stayed in the cabin for about two months, due to a blizzard and a snowed in conditions.

Two track roads turned to the bottom of Park Wash. We knew we would join a more established dirt road eventually, but for now we walked through the winding wash. Despite no official road, we definitely saw evidence of someone driving down there.

Somewhere along the way we missed our turn onto a main dirt road. Drew and I were looking at the map and noticed we should’ve been on the road at least a mile prior. Instead, we still wound our way through Park Wash, paralleling the road. With really no where good to climb out of the wash, we did our best to scale crumbly dirt walls covered in spiky plants. Chris, hiking most of the trip up to this point in Chaco sandals and socks, needed a moment to pull many spikes from his socks.

We had about nine miles to walk down the road. In need of water, we made a quick half mile roundtrip excursion to a spring. We then walked about a mile further down the road before tucking out of sight for the evening.

The next morning brought many things to be excited for: road walking usually means quick miles, we were approaching our second cache of the trip, and we found a little phone service to make phone calls.

The second cache was located about a half mile before US-89. We found it easily enough behind the sea of sagebrush. Clay and I dropped it off around 8PM about two weeks prior at this point. Other than partially frozen water jugs, the cache was completely in order.

As we sorted through snacks, dinners, new maps, and items to leave behind, we looked back at everything we’ve hiked so far. Drew informed us he could still see Bryce Canyon; we would be able to see it almost up until dropping into the Grand Canyon.

Crossing US-89 meant about a day of hiking remained in Utah before we crossed into Arizona. Passing motorists gave us some shocked looks as we scurried over the highway and into the start of Buckskin Gulch.

I’d been intrigued by Buckskin Gulch since I saw it on a map. Buckskin Gulch is the longest slot canyon in the southwest. Most people don’t hike the gulch to the highway, but day hikers frequently travel through Wire Pass on the southern end. We wouldn’t make it through in one day, so we camped near Buckskin Gulch Trailhead (on the national monument side) before entering Vermillion Cliffs Wilderness the next morning.

The colors and textures in this section of Buckskin Gulch amazed us. Rust colored rock cracked and rippled around us, constantly constricting and widening. We saw a family day hiking and figured Wire Pass must be close. As soon as we rounded the corner, at least twenty people appeared, starting either day hikes or backpacking trips. It was a bit overwhelming due to how few people we’d seen the past few days.

In some places the slot canyon is so narrow there’s only enough room for one person to walk through. Luckily, we avoided any traffic jams with on coming backpackers, but we would wait a few minutes at some narrower spots to let other hikers through. At one spot over ten people hiked through, eager to start their backpacking trips.

It makes sense why people like Wire Pass so much. The narrow tall canyon walls feel adventurous to slip through. The rocks glisten from seeps running down them. A ladder carries hikers up or down an eight foot climb.

The non-technical aspect of this hike also makes it easy to forget the dangers of slot canyons. Flash floods can happen without warning. We ducked under a massive piece of drift wood, probably weighing over one hundred pounds, jammed between the canyon walls. It was an interesting visual of flash flood power.

Once through Wire Pass, we hiked a couple miles down House Rock Valley Road to reach Stateline Campground and the start of the Arizona Trail. The signs near the border always make me laugh, as you exit Utah, exit Arizona, and then exit Utah again within the span of about ten minutes. We picked up three gallons of water Clay and I cached back in October. I debated whether or not to put a water cache at the start of the AZT, but I’m glad I did. Since the off trail spring back in Utah, we wouldn’t find water for about forty miles.

From here we realized just how far we actually hiked on the Hayduke Route thus far. The route map gives estimated miles, from a hiker dropping GPS way points. Finally having actual trail miles to compare to route miles, Drew estimated the route mileage short changed our daily mileage by about ten percent.

It was nice to hike on the AZT again. Drew and I had both hiked this section of the AZT back in 2019 (at different times and we didn’t know each other yet). We hiked through the Mangum Fire burn scar on our way to Jacob Lake to pick up our third food cache. Even in Arizona, Drew made sure to remind us that he could still see Bryce Canyon.

We felt cold in Utah, particularly in Bryce Canyon, but at 8,000 feet on the AZT we felt very cold. We carried our water jugs from the Jacob Lake cache, hoping if we slept with them they’d melt during the night. They did not. Drew sunned himself on a bear box while Chris melted the rest of his ice into water. We avoided camping in valleys, so we could sleep in slightly warmer air temperatures.

Our final day on the AZT was exciting because Clay would meet us with our final supply cache and hike with us into the Grand Canyon. Seven miles from our turn onto a forest service road, we ran into Clay. He was very excited to see us and had many treats to share, like cookies from Jacob Lake.

The Hayduke Route leaves the AZT at the Kaibab Trailhead, turning southeast for seven miles to the Upper Saddle Mountain/Nankoweap Trailhead. Located on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, the Nankoweap Trail is known for it’s remoteness and difficulty.

We camped at the trailhead before sorting six days of food, pack rafts, and paddles the next morning. It’s too bad we didn’t see anyone else on that trail because we looked ridiculous with all of the pack raft gear strapped to our packs.

I asked one of my hiking partners, who hiked Nankoweap Trail before, how it compared to other non-corridor trails in the canyon. He said it was definitely the hardest trail in the canyon, with very steep grades and a few narrow spots of trail less than a foot wide. Once on the trail we decided the entire trail trail was less than a foot wide and lived up to the “very steep” claim. We already moved very slow with the extra eight to nine pounds of rafting gear, so our trip to the bottom moved at a snail’s pace.

A couple facts about Nankoweap Trail: Originally, this trail is a route for Native Americans to access the river. In the late 1800s horse thieves used to move stolen horses down this route, ferry them across the river, and hike them out the Tanner Trail. We have no idea how any horses made it down that trail with the steep grades and short rock scrambles.

We arrived at Nankoweap Creek around 5:30PM. From the creek it looked like the canyon leading to the Colorado River was “just around the corner.” We were very wrong. With an early sunset, we spent about two hours hiking in the dark down the creek. Relieved to finally arrive at the river, we hastily ate dinner and set up camp.

Nankoweap Beach is a popular stop for river trips travelling down the Colorado, with a few locations to camp. We wondered if we’d share our camp with any river trips, but as far as we could tell, no one stayed there that night. We were convinced though we could smell the smoke of someone’s cooking.

The next morning brought a day we all looked forward to; our one and only zero day (no miles hiked) at the bottom of the Grand Canyon! Originally we planned to not take any zero days, but part way into the trip Drew asked if we could take a zero day so Chris could tell us about the Nankoweap Granaries tucked into a cliff near the river. We also desperately needed a break. We had hiked over 200 miles over eleven days; the mileage and cold weather was starting to take a toll on us.

The start of our rest day did not disappoint. The sky was cloudy and moody from a small storm earlier in the morning. We enjoyed breakfast on the beach and the guys went for a quick, chilly swim in the river. A relaxing start to the day proved exactly what everyone needed.

Now time for the archeology lecture. After packing up camp, we moved about a mile west along the beach to the trail junction up to the granaries. Along the way, we stopped to look at some pottery shards found by Clay. Chris told us all about different pottery types from different time periods and then we left them where we found them. From the junction, we dropped our packs and climbed up to the granaries. Built by Ancestral Puebloans, the granaries helped store and protect food.

The view looking down river is my new favorite view in the canyon. The colors and lines of the canyon are beyond dazzling.

Once we finished looking at the granaries, we hiked back down to our packs. We planned to move camp to the western end of Nankoweap Beach and enjoy the rest of the afternoon. Technically we hiked about a mile and a half on our “zero day”, but it’s a minor detail.

Chris was particularly excited about our up coming section of this trip due to the river crossing. Obviously we all paddled on a raft at some point since we all made it out the South Rim, but Chris did a bit extra. This next part gets into the weeds of logistics a bit, but I think it helps show why Chris arguably had the most exciting Hayduke trip out of everyone and exactly what he did.

Crossing the Colorado with a raft in the Grand Canyon requires a special addition to a backcountry permit. The Park Service will likely send you an additional permit application requiring more detail because they have questions about where you’re going. Backpackers are only allowed to raft if their route requires crossing the river where no bridge is available. When crossing they’re only allowed to travel a maximum of eight miles down river. All rafters are also required to wear a certified Class III or V personal floatation device (PFD) when on the river. While many sections of river we hiked past flowed calmly, the river quickly changed it’s tempo as the depth changed and underwater drops occurred. A few rapids along this eight mile section range in difficulty between Class II/III rapids. Even outside the rapids the river may flow swiftly, with rougher waves and riffles.

Chris has planned his own multi-day river trips and comfortably runs class III rapids. With a fairly robust raft, tougher material on the bottom of his raft allows him to float over rocks and self bailing holes prevent his raft from taking on too much water. With the distance down river we planned to hike exactly eight miles, Chris was very interested in potentially running that entire river section. He took his raft above Nankoweap Rapid (an easier Class II) as a test run and floated about a half mile back down to our camp. It was a pretty easy decision for him to float the eight miles the following day.

The rest of us had a much lazier afternoon. Reading and just lounging by the river is a great way to enjoy the canyon. I hadn’t brushed my hair in since the start of the trip and decided now was the time to tackle that problem.

The next morning we left camp early. Between about nine miles of traverse heading west in the canyon, crossing the Colorado, and fording the Little Colorado, we had a lot to do that day. Packed up in his raft, Chris would do his best to keep us in sight as Drew and I made our way through the traverse. Clay headed back up Nankoweap to retrieve his truck. He planned to drive around and meet us on the South Rim on our final day.

About an hour into his hike out, Clay came across two people hiking down Nankoweap. Surprised to see anyone and not seeing anyone outside our group for two days, he stopped to talk to them. He explained he was helping some friends on the Hayduke Trail and they asked, “Oh, is it Elizabeth and her group? We saw her name in a couple trail registers. We’ve been trying to catch them for the past few days.” Convinced we wouldn’t see any other Hayduke hikers the entire trip, we were surprised to later hear of two of them only a couple hours behind us. They didn’t have pack rafts and instead planned to hitchhike with a passing river trip. Since we didn’t need to wait for a river trip, we would suddenly be at least a half day or more ahead of them again.

Drew and I were a little worried about the traverse section on this trip. Earlier in the year, we tried traversing a section of the canyon up near Lee’s Ferry. Extremely challenging, the route finding and terrain was one of the hardest trips we’d even done. And that trip was only eleven miles one way.

After a little trouble, Drew and I found a path contouring along the river. We were surprised at how good a path we followed; a night and day difference from the year’s earlier canyon trip, we suddenly were making good time.

While Chris went through Kwagnut Rapid (Class III) to start, a lot of the beginning of his trip consisted of mostly calm water. Feeling a bit jealous and also in possession of a raft, I decided to join Chris at the next point we could get down to a beach.

Chris helped me sort all my gear to keep it dry, evenly distributed the weight around my raft, and tied it securely. The last thing you want is to lose all your gear in the river. The plan was for us to stick together, while Chris explained river characteristics to look for when rafting. He also went over general best practice guidelines when rafting, such as wearing rain gear instead of hiking clothes. In case you flip, you have dry, warm clothes to put on immediately after to help avoid hypothermia.

Naturally, as soon as I started rafting the river started flowing a little swifter. I would follow Chris’ path through the faster riffles and simply do my best to keep the raft pointed down river. We also pulled over a couple times to empty water out of my raft, since I don’t have self bailing holes. I only almost fell out of my raft twice. Overall, rafting was such a blast and one of my favorite parts of the trip.

I only rafted about a mile with Chris before rejoining Drew. There was a beach for us to pull over and wait for Drew, since we’d passed him with the faster current. Looking at the map, 60 Mile Rapid (a more challenging Class II rapid) was only a mile ahead. Everything Chris and I rafted was easy and generally low risk. Not guaranteed an opportunity to get out of my raft beforehand and with no interest in accidentally going through the rapid, I rejoined Drew here.

Rejoining Drew, the traverse became more challenging and reminded us of our previous canyon adventure. Not necessarily on a path anymore, we did our best to pick out the most logical route heading down canyon. Tiny rock cairns appeared every now and then in the oddest locations, convincing us they could’ve only been placed by previous Hayduke hikers.

We also walked along some giant rock shelves above the river. Easily the coolest part of the traverse, Drew and I hiked along with Chris floating below us. Drew commented that if the entire Grand Canyon traverse was like this section it would be a piece of cake. If only…

Shortly after the rock shelves, we came up to 60 Mile Rapid. A good thing I exited my raft when I did, we never saw another location further down canyon to pull a raft over. We stopped to watch Chris run the rapid, hooting and hollering the whole way down.

Now past the rapids, we were a mile from the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. We found a beach with a calm piece of river to set up both rafts and start shuttling everyone and their gear. Chris and I paddled across first. He then towed my raft, along with the paddles and PFD back for Drew to cross. Overall, the entire shuttle went over without any issue.

Surprisingly, the river crossing was not the most difficult part of the day. We still had one more mile to travel to the Little Colorado and it was definitely the most difficult. We passed packs on a steep down climb before scrambling down ourselves. To bypass a cliff, we determined that the fastest (not necessarily the best) way was to wade in the Colorado. This required us to hug the cliff while trying to not slip off the narrow underwater shelf into very deep water. Definitely not our smartest moment, but we made it to the Little Colorado.

Fording the Little Colorado was an interesting challenge in itself. Hikers must travel a quarter mile upstream before wading and can only wade during certain times of year to avoid damaging native fish habitat. We also couldn’t use our rafts because water craft isn’t allowed on the Little Colorado. The river is deep in many spots and can flow swiftly. We ended up crossing a fast moving section that came up to my hip pockets. Moving slowly and as steady as possible we all made it to the other side.

Still not quite done for the day, we found the Beamer Trail and hiked a little over a quarter mile to a beach to camp. No camping is allowed within a quarter mile radius of the confluence for it’s protection.

The next morning felt anti-climatic compared to the day prior. We hiked the Beamer Trail to Tanner Beach. A popular beach for backpackers and river trips, we felt a little shocked by the increase in people. Two older gentlemen, curious about our paddles, asked what kind of trouble we’d been up to. Former backcountry guides for the canyon, as soon as we said we’d crossed the Colorado they knew we’d come down Nankoweap Trail.

From Tanner Beach we picked up the Escalante Route, my favorite trail in the canyon. Hiking late into the afternoon and early evening, we made camp at the best piece of flat ground we could find. Not our best night, the wind howled all night and into the morning.

That day we also started discussing if we wanted to hike all the way to the South Kaibab Trail or end a day early and hike out the Grandview Trail instead. All very tired at this point, the excitement of packing rafts and paddles was wearing off quite quickly. Our food bags also started to look a little slim and we didn’t like the idea of rationing our food for the next couple days. It didn’t take much to sway our decision to change our trip at the end.

The next day was the only day of rain we had the entire trip. Sporadic at best, it would rain hard enough to convince us to don rain gear and then promptly stop ten minutes later.

The sky was impressive the entire day though. Dark gray clouds rolled through the canyon in the morning. Blue and violet clouds seemed to glowed as the sun tried to poke through. As soon as it seemed like the clouds would clear up, more appeared.

This part of the Escalante Route is my favorite section of the Grand Canyon. We hiked down into 75 Mile Canyon early in the morning before it started raining. Next we hiked up the ledges to one of my favorite views of the Colorado. We carefully traveled down the rock slide to Hance Rapid. Hance Rapid is at the mouth of Red Canyon.

From Hance Rapid we started following the Tonto Trail. The Tonto Trail is interesting in the beginning as you climb to the Tonto shelf and that’s about where it ends. Once on this shelf, hikers travel in and out of every drainage and side canyon entering the Grand Canyon. Over and over again. While some of the larger side canyons (like Grapevine) are neat, regardless you’re sill going to hike about three miles up the drainage side and then about three miles back to get around.

Once through a couple smaller drainages we started to see signs for the Grandview Trail and Horseshoe Mesa. Our final campsite for the trip, Horseshoe Mesa is about three and a half miles below the rim.

I’ve hiked the Grandview Trail once before several years ago. I don’t remember it being as steep and rocky as it is, but that’s what we got to hike through. With only a mile to go and in the dark, Chris and I definitely complained the entire way up. It was getting to be that point in the trip. Drew had gone ahead to find a place to camp.

Grandview Trail and Horseshoe Mesa is known for caves and old copper mines in the area. Hiking past large, dark mine shafts when it’s almost dark really helped Chris and me pick up the hiking pace. Already eerie looking, we weren’t interested to see if any animals lived in the mine shafts.

The final morning began with me waking up to Clay crawling under my tent vestibule. He woke up very early to catch us before we started our final climb out of the canyon.

We took our time on the climb. As much as we were ready to finish our trip a small part of us naturally wasn’t ready for it to end. I was also taking my time because it was steep.

As we got closer to the top the number of people gradually increased until we came around the corner to a large group. We were now less than five minutes from the top. Rafts, paddles, and all we made it to the end of our trip. Over 250 miles, we’d been out hiking for seventeen days.

A little footnote should be made about Drew. While Chris and I downloaded maps on our phones for the entire trip, Drew did not. Drew navigated the entire time using map and compass skills and keeping track of which direction we turned. He also didn’t turn on his phone the entire trip.

It always feels weird to end a big trip and go back to normal life. Usually about a week after being back I feel ready to go out on another adventure. Maybe one day I’ll figure out how to make that “normal life.”

We have plans to finish the rest of the Hayduke Trail at another point, but for now it’s on hold. With other trips in the works and another that’s already passed (that trip write up is coming next) we’ll always have plenty to keep us busy. It’s fun to work on the trip write ups during the lull, but you can always be certain I’m working on something in the background.

I hope you enjoyed reading this trip report as much as we enjoyed the trip. I know it’s kind of a long story. But I honestly think you can never have enough to say about the southwest, it’s just that fantastic!

And since we’re on the topic of never enough to say about the southwest, trip reports coming up next are a few Superstition Wilderness adventures and Drew and mine’s former Grand Canyon misadventure.